Evelyn Schalk ◄

English translation by Dörte Eliass

Chronology of a broken promise

Amena Karimyan often feels closer to the stars than to other people. And it’s no wonder, because the path of this 25-year-old, who is Afghanistan’s only female astronomer, has been a rocky one from the start. When the Taliban seized power, that path put her life in danger. Austria granted her a visa, and a shimmer of hope flashed before her eyes. But suddenly darkness falls on her. Amena Karimyan, whom the BBC just selected as one of the 100 most influential and inspiring women of 2021, is trapped. Upon her arrival in Islamabad, the Austrian authorities withdrew their visa confirmation and abandoned her. Now the young scientist, women’s rights activist and author has no way forward or back and her situation is deteriorating from day to day.

“If I don’t get out here alive, please tell the whole world this story. Tell them I wanted to make Afghanistan a place of knowledge and civilization. Tell the world there were many like me here, but our life was short and even in those few years, we were betrayed. Tell the world Afghanistan has so many good people, but it was sold to a handful of traitors. Tell them I set off on my path of dust and blood with so many dreams and I couldn’t even say good-bye to my family. Tell them I didn’t even get one chance to play the song of reconciliation and peace on the violin that a friend gave me to fulfil my greatest wish.”

Amena Karimyan writes these lines in the early evening of 19 August, 2021 from Kabul. She has been in hiding for weeks; she hardly dares to leave the house. She doesn’t know whether her life will go on, and if so, how. A life she’s already had to fight for almost every moment. Afghanistan, the country where this young woman of 25 built an existence against so many odds, where she made plans, the country she hoped her work would help to advance, is falling to pieces around her, more quickly than she or anybody else thought possible. The radical Islamist Taliban are capturing one city after another; fear of the horrors of their regime, which had been in power until 20 years ago, pervades every word, every movement, every glance. “We’re not going back 20 years – this time it’s a whole century,” says Amena in stunned desperation. Those from the generation between twenty and thirty who don’t want to join the religious fanatics are losing everything they fought and worked for their whole lives. With them, a country loses its future.

Herat too has fallen; with its 630,000 inhabitants the provincial city is more than double the size of Graz. Amena was born here; she has lived and worked here until quite recently.

Over the weeks and months that follow, the two of us will form a bridge between the two cities: she, having fled Herat only to get stuck in the nowhere between the worlds, and I in Graz, trying to find a way to bring her, her knowledge and her experience, gained so early in life, across that bridge. At a time when the pandemic of distance is adding fuel to the already rampant pandemic of isolation and making the fences and walls around Europe grow even higher, two women who didn’t know each other before will become “two friends from two different worlds,” as Amena says much later. The barrier between those worlds is not our different language, history, religion or culture, but only the walls that prevent us from encountering and understanding each other. That’s what we want to change, as scientists, authors and human beings.

30 July – from Herat to Kabul

It is 30 July, 2021, and the Taliban are advancing quickly; soon they will capture Herat. Amena packed her things long ago, now she joins a small convoy of other people who are leaving the city in a hurry. Amena’s family is in Herat – her parents, her five sisters with all their nieces and nephews – her friends, her books, her notes, her home. She leaves everything behind from one day to the next to flee to the capital city of Kabul. She’s also deleted her social media accounts; the fear of being recognized is too great. She sets off for Kabul without even saying good-bye to her father. Whether she’ll ever see him or anybody else from her family again is written in the stars.

Amena developed an early fascination with the stars, which increased despite all the obstacles in her way. She has absorbed everything about astronomy, read what she could find and later joined local discussion and research groups. She was almost always one of the youngest people there – and the only woman. Amena wants to study astronomy, since ‟astronomy is the lived language of the universe”. But that’s not an option in Afghanistan; there’s not a single astronomical or astrophysical institute. So she decides to study engineering while working in various jobs and financing her studies herself – that’s important to her. There’s hardly anything Amena hates as much as dependence: as a young woman in Afghanistan she’s had far too much of that even before Taliban takeover. Nevertheless she selects a technical course at university. Everybody tells her that men would be better at it. She is subjected to name-calling, mockery and scorn on a daily basis, and even attacks. She refuses to wear a burka and reduces even the obligatory chador to its essentials. That also exposes her to contempt and danger. Her other passion is literature; she recites poems, but she also increasingly writes against the suppression of women and reads her work in public. She discusses things with her male work colleagues and fellow students; she walks through the streets engaged in debate. What seems so self-evident in other parts of the same world, not even worth mentioning, costs her a tremendous amount of strength, endurance and courage each day. In 2017 she completes her studies as a civil engineer. As such she is interested in how cities function, in the use of resources, economic questions and concrete solutions to problems. She works on an EU infrastructure project until July 2021 at Herat city hall. She wants to help her city develop, to tackle its many problems. Even before that, she had been organizing brown bag lunches for street children, registering girls at school and encouraging them not to drop out again. She also dedicates herself to protecting civilians during the war.

But she never gave up on the stars. In 2018 she founded her own organisation “Kayhana”, which in Dari means something like “small universe”. Amena writes: “Living on this earth, you don’t recognize that this is our common home. You only see that when you leave it and observe it from above as a whole. It’s the Earth that makes life possible for us humans in the first place, with its microcosms, the way it moves around the sun, its oxygen, gravitation, the ozone layer and its atmosphere, the nutrition-rich soil and the water that we all need. That’s why it’s so important to combine our efforts to preserve this home.”

Kayhana opens doors to her, which she in turn opens for other young women. For the first time she establishes international contacts and gains access to a worldwide network of astronomical institutions. The group successfully takes part in competitions. Kayhana and its successes, as well as her public commitment to the rights of girls and women, soon earn her a local media presence – and thus the wrath of the Taliban.

Weeks later, at the border, they will look with contempt at her scientific books and tell her that a woman who carries something like that with her only deserves to die.

Through her public presence, I too became aware of Amena and her love for astronomy. When the Covid-19 pandemic began, we in the ausreißer editorial department initiated the interview series Stimmen aus der Krise, Stimmen gegen die Krise [Voices from the crisis, voices against the crisis], so that long-distance communication could be intensified rather than stopped. In time, this resulted in long-term collaborations and an exchange on multifarious levels. We are experiencing how big the current gap is, and how great the need is for well-founded information and more in-depth perspectives that facilitate real understanding.

With the situation in Afghanistan deteriorating rapidly, we realize we have to act quickly. We coordinate with colleagues from cultural and scientific institutions, the Styria cultural city network, the esc medien kunst labor, institutes of the Karl Franzens University Graz and finally the Austrian Academy of Sciences. Only now do we realize how much immediate interest there is, and how many connections are available from different groups at different levels. So we bundle the invitations for Amena Karimyan to Graz and Vienna, we make joint plans for exchange, lectures, research opportunities. One thing is clear to us all: her voice should and must be heard. In Austria’s media, almost all we hear about Afghanistan is how many were killed in the latest bomb attack. Of course, there is also an awareness of the massive disadvantages women face. But very few people know or can imagine what that means in practice, especially for a young woman trying to establish herself as a scientist. And vice versa, the situation has had massive effects on social, scientific, and artistic developments. In 2021, those effects are in no way limited to certain locations.

Because the first thing Amena Karimyan has to do to reach her goal is leave Afghanistan. Thousands of men and women are trying to do exactly the same thing during those days and weeks. Amena does not fit into an existing evacuation programme – she’s never worked for international militaries or corporations. We turn to the Austrian embassy in Islamabad, which also looks after Austria’s affairs in Afghanistan. Amena has all the papers for a visa application, but an application like that could only be filed in person, we were told. But how to cross the border? Pakistan closed its border long ago and the Taliban are setting up one checkpoint after another.

15 August 2021 – Kabul falls

On 15 August 2021 the Taliban capture Kabul. The whole world seems horrified at how quickly the capital city falls. The next day a message comes from Amena, more desperate than ever: “The Taliban are entering our house, they are here, now!” Together with other women she hides in the upper storey of the house where she has found refuge in Kabul. Minute by minute, she describes what happens via WhatsApp. “They’re searching the house, they’re filming. I hope they don’t come into our room.” I am trembling. I sit 5000 kilometres away, I am present and at the same time endlessly far away. I can hardly imagine what she’s going through at that moment, I’ve never experienced such fear, nor such powerlessness in all its immediacy. “There is a huge amount of chaos. It is horror.” They take what they need, outside they take away the weapons of the security guards of the complex. Finally they withdraw. But they say they will come back.

Until now we’ve communicated almost exclusively in writing, but now I can’t take it any longer – I call her up. I am tremendously relieved when I hear her voice.

Amena’s mother tongue is Dari, closely related to Persian and Farsi. Although most of the theoretical books of her faculty are written in English, she never had an opportunity to speak the language. That, too, is often a privilege of men. Nevertheless we communicate via WhatsApp in English, enabled by GoogleTranslate. Since for my part I hardly know a word of Dari, I can’t read a single letter. She will try to teach me individual terms during the long days and nights of waiting, but the structure and the sound are so complex that I can hardly remember anything. She, on the other hand, will have to communicate entirely in a language she doesn’t speak and which isn’t hers to save her life and that of her family.

The Austrian embassy takes action and includes Amena on the list of people they want to help leave the country. The precondition: she must come on her own. As opposed to other countries, Austria does not send any planes or convoys for evacuation. The diplomats can only help with crossing the border. The only way left is by land, nobody asks how.

19 August – if I don’t make it out of here alive…

Language, the city, the people she loves. Now the moment of the decision has come. I’m afraid to give her advice, afraid to encourage her but also afraid not to. I can’t judge the situation and I tell her that. ‟You didn’t let me die inside, that’s so important for me”, she writes to me. Her family doesn’t want her to embark on the journey on her own, but Amena gets her own way again. While I’m afraid for her life, no matter what she decides, she has made her decision. She will go. Finally her family agrees, too. Amena will make the journey to Pakistan alone, risking her life. She fulfils the Austrian embassy’s condition.

In the meantime, a rumour spreads that the Internet will soon be cut off. How will we keep in touch then? It doesn’t happen, but the fear is there, no day passes without bad news and there are countless rumours. How to differentiate between true and false? As quickly as the rumours emerge they disappear again, and so we as journalists find it difficult to check how much truth they contain; sometimes it is simply impossible. But they do have an effect. They wear people out even further who already fear for their lives. They fuel mistrust and fear.

Now Amena’s family insists that it is time to leave. The fear that something will happen to her is growing every day. News about the situation at the borders can hardly be verified, either. Who gets through, and when and how, can change within hours.

24 August – to Torkham, first attempt

On 24 August, Amena makes her first attempt to cross the border. From Kabul to the next border crossing in Torkham, it’s a drive of over six hours on unsafe roads with many Taliban checkpoints. Her sister’s family brings her to the border, well aware that they have to go back themselves, accompanied by her sister’s little son who is only two years old. They start on their journey and I hope desperately that they will survive it unharmed. On the other side the driver, whom we arranged through private contacts literally halfway around the world, is waiting in vain to take her from Torkham to Islamabad. Again and again she tries to convince the border guards, again and again she is rudely rejected. She keeps me informed via WhatsApp, for hours. I desperately text the embassy and ask for support, which is granted. But it seems to have no effect. Evening comes and Amena is still not on the other side. It’s too late to go back to Kabul, the trip would be too dangerous in the dark. They move into a room in a guesthouse near the border crossing. It is dirty, noisy, they are shouted at and threatened. They will have to change rooms three times that night, for fear of attacks. I hardly sleep – sitting here in safety, did I give her wrong advice? How could I expose her to even more danger! Did I do that? The next morning she asks desperately what she should do. I have no idea, at the embassy nobody can tell me whether it will be possible to receive a permit, and how. But she can’t stay here waiting for days; neither can her sister and her family. Totally exhausted, they return to Kabul. Her little nephew falls ill.

30 August – the last US plane takes off

On 30 August the last US plane takes off from the airport in Kabul; the air space is now deemed “uncontrollable territory”. What remains is a broken country and millions of people in fear and desperation. At night, Amena sends me videos, in the darkness lights are flashing at the starless sky, shots and explosions can be clearly heard. She has been past bearing those noises for a long time. “All of us are panicking; the whole city of Kabul is awake. We can hear shots everywhere. Around the airport, the people are fleeing from their houses, but nobody knows where to. It’s worse than ever. The Taliban are celebrating with the blood of the people.” These are winners’ shots fired off by the Taliban. Later we will be able to read how many people died in the blaze of gunfire.

5 September – a visa for Pakistan

The Austrian embassy negotiates a Pakistani visa for all those who are on their lists. Amena finally receives her visa on September 5. When she collects the paper at the counter of the Pakistani embassy in Kabul, she trembles, this time for joy. She is relieved beyond words. For the first time, she has a tangible hope.

9 September – to Torkham, second attempt

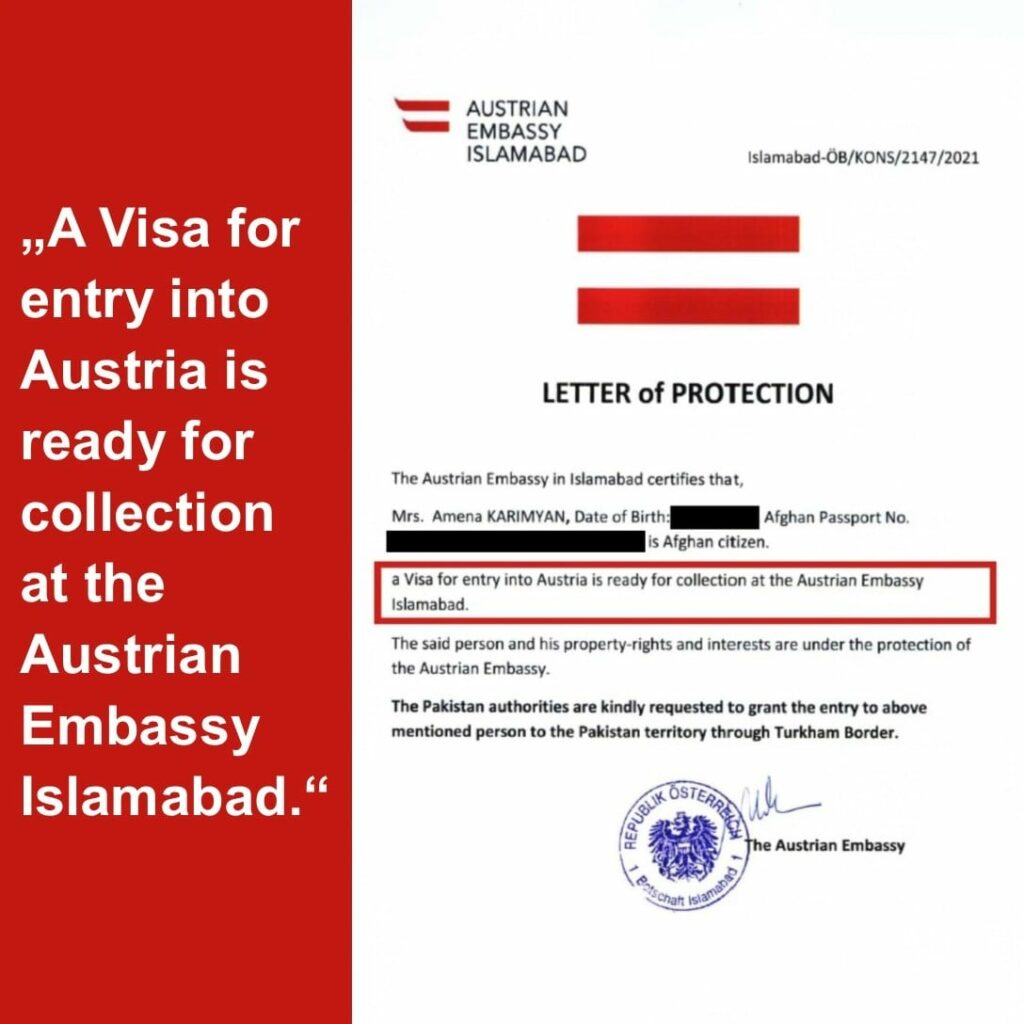

Soon afterwards, she sets off for Torkham a second time. Once again she faces dust, dangerous streets, an hours-long drive past armed checkpoints towards the border; on the way she passes walls plastered with Taliban advertisements for Koran schools and, again and again, their black-and-white flags. But this time she has a “Letter of Protection” from the Austrian embassy in her luggage, which states that “a visa for entry to Austria is ready at the Austrian embassy Islamabad”.

Under this precondition the Pakistan ministry of the Interior agrees to let her enter the country. But when Amena Karimyan arrives in Torkham on 9 September, she experiences the same thing as last time – only worse. At first the Taliban send her back, again and again. They shout at her wildly and threaten her with violence. She repeatedly draws attention to the Austrian letter of protection, but gets no further.

In the end, they let everyone who is waiting pass through – except her. She is angry and desperate. As a Dari-speaking Tajik, she has been exposed to massive discrimination all her life and treated as a second-class citizen in her country. And now, on top of everything, they want to prevent her from leaving it. But there’s no support from Pakistan either, quite the opposite. “All our spirits are broken. On one side the Taliban who order us to wear the hijab and hold weapons to our foreheads. On the other side a Pakistani soldier who doesn’t want us to cross the border,” she writes bitterly. She waits hours in the blazing heat, her whole body covered, wearing a woollen mask. Her cell phone battery is almost dead, there is no electricity there. She sends me the number of her brother-in-law, who has come along, again with her sister and the little nephew. Eventually, her nerves are shattered. “Evelyn, I can’t bear this any longer, I’ll go back to Herat, no matter what happens to me. I can’t do this to my sister any longer.” I beg her urgently to wait. I’m aware that the embassy is working on the case but at the moment nobody is answering our desperate calls. I am torn, once again – am I giving her the right advice? Am I causing even more danger for everyone? I can’t very well let her go back now. I have the confirmation from the embassy that the Pakistani side has consented to her crossing the border. So why can’t she get through now? Why is there nobody to help her? Once again she takes the initiative at a nearby car park and charges her cell phone from one of the cars. The embassy asks her to wait. They don’t say how long. An “Urgent Letter” is being prepared. This letter is meant to help convince the border guards. Eventually they send her a “note verbale”, in which the Pakistani authorities are urgently requested to let her cross the border as a “citizen who will receive an Austrian resident permit”. ‟The Austrian authorities take full responsibility for Ms. Karimyan leaving Pakistan as quickly as possible.” Again the Ministry of the Interior of Pakistan agrees and gives instructions to let her pass. Only, nothing happens.

Amena is in a panic. She’s the only woman around, she is subjected again and again to the glares and threats of the Taliban. It’s evening, too late to drive to Jalalabad, the nearest large city. Again they take up quarters in the same guesthouse. Again she stays awake. The Taliban go from door to door, making noise, making threats. Nobody sleeps. We stay on WhatsApp all night. She tells me about Kayhana, about the girls’ enthusiasm, she sends me photos of their meeting. At some point the conversation drifts to literature, her first manuscript that she published together with a colleague, she talks of books she’s read and we find an astonishing number that we both know. Here it is long after midnight, in Torkham it’s around four o’clock in the morning. She’s already been awake for most of the past few nights. Finally she promises to sleep at least a little. I can’t keep my eyes open; when I wake up two hours later, she’s still online.

10 September – across the border

At six o’clock in the morning, I read Amena’s message that the Taliban pushed her back with weapons drawn, held the gun to her temple and threatened to pull the trigger if she took another step. ‟Nobody dares to say a word here, the answer is only ever weapons.”

Her panic grows but she continues to wait. She sits down. Three Taliban come around, they shout at her, one strikes at her with a whip. Her whole body trembles, tears of fear and desperation. She just wants to leave, it doesn’t matter where. They are following her back to the guesthouse, they keep shouting at her, they threaten. Her sister yells at her to get away. A life-threatening act of desperation. I’m sitting in my safe living room, reading almost everything in real time. I no longer know what to do. What am I doing here, while she fights for her life? If something happens to her, I’ll never forgive myself – I’ll never forget these days as it is.

She continues to try. Late that morning, the connection suddenly breaks off. Then, finally, a message. ‟The Taliban have arrested me.” I’m shocked, what has happened? She doesn’t answer. Five minutes, ten minutes, half an hour. An hour and a half later a message from her blinks on the display. The Taliban arrested her, brought her to their leader, took her information and scanned everybody’s papers. She is unable to describe what else they did. She seems to be between the borders. Her phone battery is almost dead again. Then I don’t hear anything for two hours. An eternity.

The driver on Pakistan’s side sends the reassuring message. He’s been waiting for her since early morning again. She made it, she’s on the other side of the border! I can’t remember the last time I was so relieved. Amena’s phone is connected to the Internet again, too. I write to the embassy immediately and learn that Amena has already contacted them herself. She’s got through the worst part. There’s not much that can go wrong now – I think.

Through acquaintances, we’ve organized a safe hotel for her where she can first take some time to recover. But is that even possible? After everything she went through, she’s stranded in a foreign land, and she doesn’t speak Urdu, the language of Pakistan. She’s outside of Afghanistan for the very first time, and she’s completely on her own.

16 September – first interview with the Austrian embassy

Three days after her arrival, she is notified of her first interview at the Austrian embassy. In contrast to earlier information, which advised her to apply for a category C visa for three months, she is now asked to bring along the documents for a category D visa. At first we are delighted, because that visa is valid for six months and gives her more time for her activities in Austria. She confirms the date immediately and prepares meticulously. I help her on WhatsApp with explanations, when bureaucratese gets the better of Google Translate. She quickly collects all the necessary documents, finds a copy shop for the required copies. When she sets off for the embassy on 16 September, she’s also carrying saffron from Herat as a small gesture of thanks for their help. She’s nervous and afraid to make a mistake, the situation is completely new to her. At the same time she is delighted to finally come to Austria. She’s curious about the exchanges she can have with those people who have invited her; she asked me earlier for all the details about the professional specialties and interests of each person, what the institutions do and how the organizations work. But her thorough preparation for her stay is mirrored by her lack of experience with bureaucratic procedures.

When she gets in touch after the conversation, she is beside herself. She couldn’t answer all the questions. Yes, naturally she wants to come to Austria, to accept her invitations, what else? Naturally she wants to use her time there to improve her knowledge of languages. What comes afterwards? How is she to know now? She’s just escaped from the horror of the Taliban and she’s terribly concerned about her family who will now become even more of a target after the excitement she has caused. She has no idea what she’ll be able to do and what she won’t. How is she supposed to explain what will happen after six months? ‟Evelyn, I feel so helpless.” The saffron is still in her bag, which she had to leave at the entrance.

She was asked to submit further documents. So she does it on 24 September; the same email contains an interview application form for a follow-up conversation.

On 1 October, the embassy answers with a standardized email that contains another link to a form for booking an interview. She again fills this out as required and sends an email in response on the same day.

In the intervening days, she carefully puts out feelers and again it is her passion for the expanses of space that gives her courage. The young scientist gets an overview of astronomical institutions in Islamabad and finally meets a group of Pakistani astronomers for their nightly observation of stars – but not without considering security questions first; her fear of attacks looms large here, too. Shortly before she leaves her hotel room, she sends me a photo of herself wearing jeans, a T-shirt, and uncovered hair. ‟I wish I could go out like this”, she writes underneath.

October 12 – second appointment at the Austrian Embassy

There’s no news from the consulate. She is getting more and more anxious. In response to an inquiry on 6 October, they say that the form for Visa D is still missing. They don’t mention the email that had all the requested documents attached. But Amena finally gets her appointment for the second interview.

On October 12, she is supposed to bring the form with her again. So she fills it out conscientiously for the third time, this time by hand, and presents it at the consulate, along with all the other documents. Once again, she does not know what to expect, but she does know that her life depends on the decision of the people she is about to meet again.

But this time they are different staff members, and the conversation is completely different, she reports shortly afterwards. They told her that she only had a 50:50 chance — and gave her another form, this time for a category C visa. She received no answer to any of her questions, no explanation, nothing. Just the form again. She returns it, completed, to the embassy an hour later.

October 13 – the denial

Now the embassy reacts quickly. They ask her to come back the very next day. But now they won’t even let her in. At the entrance, she is handed a letter to sign. It is a denial of her visa. The reason stated in the letter: There is no guarantee she will leave Austria after her visa expires.

She is in shock, completely at a loss. At some point she will write to me: “I thought maybe I just don’t deserve to come to your country. Maybe I really am that worthless. Having your self-worth totally destroyed is worse than despair. It kills you from the inside.” Her tone has changed, her absences are getting longer. I’m getting worried. Rightly so, as she will admit to me quite a while later. “For a while I thought about suicide.”

She’s lost everything for the second time in a few weeks. But this time it’s not her past that’s been snatched away from her, it’s her future.

I am deeply ashamed. What’s the point of our horror at the Taliban if we slam the door in the faces of those fleeing their threat? Do women’s rights in Austria really only apply to those who happen to have been born with the right passport? How can the government of a constitutional state make vital written promises and then ignore them without comment? Assurances not only to a young woman in danger, but to the authorities of another state, Pakistan?

25 October – appeal

She finally appeals the decision on October 25, enclosing three invitations from renowned institutions in Croatia, Serbia and Canada/USA as evidence of her travel plans. All of them concern the period after the expiry of the visa she applied for.

10 November – denied again for the same reasons

But even that leaves the authorities cold. On 9 November, they call her again and ask her to come to the embassy the following day. On the morning of 10 November, she is again handed the new denial letter without a word. It’s all in there — that’s all they tell her. The reasoning is almost identical to the first denial. Exactly two months ago today, on 10 September, she escaped from the Taliban. Now she’s trapped.

Trapped

For Amena, returning to Afghanistan would mean death. Her border crossing not only attracted the attention of the Taliban, but more importantly, their anger. How could this young woman dare to do such a thing and insist on her freedom? But now even that freedom seems illusory. As the weeks have gone by, news about the devastating situation in Afghanistan has not abated. Girls are banned from school, universities are closed, an unprecedented new dress code for women is introduced, which outdoes even the burqa in hiding their humanity under black fabric; people are whipped, abducted, murdered. Public executions are taking place in Herat and the smallest resistance is nipped in the bud by the Taliban. Amena’s friends and family flee, disappear, hide in panic from their pursuers. Gradually, reports of attacks in Pakistan begin to pile up. When a civilian engineer who worked for the municipality of Kabul is shot dead in the street in Islamabad, Amena lives in fear for days. The world has been aware of how active the Taliban are in Pakistan at least since the attack on Malala Yousafzai. Now, almost ten years later, they are back in power.

Raising her voice As both a journalist and an active participant, I am aware of the need to tell this story. But my personal involvement makes it impossible to do so from a professional distance. And so I ask colleagues for their opinion. Everyone to whom I describe the events is horrified. How could the responsible parties put Amena in such a position? The media pick up the story and start reporting. On 22 November, SOS Mitmensch launches a petition, which is handed over to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs as an urgent appeal on 16 December. In less than a month, more than 7400 people have signed the demand to immediately issue the young astronomer the visa she was promised and to bring her to Austria. Numerous expressions of solidarity arrive, the first one is from Elfriede Jelinek: “The worst thing I can imagine is to hold out your hand to someone who’s drowning and then pull it away at the last moment. To give someone hope and then refuse to save them at the last moment. That’s what the Austrian Foreign Ministry did to Amena Karimyan,” the Nobel laureate in literature said. She is deeply outraged. “We already have enough women and enough researchers, we don’t particularly need any more, not even for a few months. Maybe that’s what they were thinking. And we don’t need women’s rights activists here anyway. Who needs them… The poor young woman must immediately get the support she was promised. There’s no question about it.”

Prominent actor Cornelius Obonya sees the Foreign Ministry’s behaviour as “unacceptable.” He explains, “It shows contempt for her, it shows contempt for the situation of people who have to flee and last but not least it shows contempt for Austrian scientific institutions.” Author Eva Rossmann also finds this to be the case and sees a “double scandal: using the terror regime of the Taliban as a pretext to disinvite her. A young woman who relied on official Austrian institutions is left to her fate without protection. To quote President Van der Bellen: That’s not what we’re like! Let’s hope so.”

Erika Pluhar sums up the situation: “To suddenly withdraw a visa promised by the Foreign Ministry due to fears that someone found worthy of entering Austria from Afghanistan might prolong their stay out of necessity — what misanthropic behaviour that shows. Amena Karimyan wasn’t invited here for no reason. She was invited because she was a recognized scientist and women’s rights activist. So then what does it look like for people — for women — who seek refuge in our country without the benefit of our Academy of Sciences or the University of Graz? It looks disgraceful! Austria deals with the topic of flight, refugees and acceptance of refugees in an undignified, narrow-minded and populist manner. Amena Karimyan, abandoned to her fate in Islamabad by the Austrian Embassy — despite a promise and a flight ticket — is a sad example. I am ashamed.”

A colleague on Twitter recalls, “Austria once had an ambassador in Prague who issued 50,000 visas to refugees against the explicit instructions of the foreign minister. His name was Rudolf Kirchschläger. The minister was Kurt Waldheim. That tells you everything you need to know.”

A colleague on Twitter recalls, “It’s long been the case that Amena’s stay in Islamabad, which was planned for a few days and has now lasted months, can only be financed by a private network and donations. If those run out, Amena Karimyan will literally be sitting on the street in Islamabad. She has nothing, and the few dollars she arrived in Islamabad with were spent long ago. Her parents and sisters, all teachers, have not been paid their salaries for months, and they already don’t know how they’re going to live. Poverty in Afghanistan is rapidly increasing. The United Nations World Food Program is warning of famine. Apparently 8.7 million people don’t have enough food to survive this winter. Pictures and videos of families selling their little girls for the equivalent of 15 or 20 euros are spreading through the media. But the thing is, few people care. Poverty kills more quietly than bombs.” Ursula Strauss, actress and UN ambassador for the Orange the World campaign to fight violence against women, is calling for support for the 25-year-old Afghan researcher, as is author Julya Rabinowich. “The promise made to that young woman, namely a visa to Austria, must be kept! This is about credibility, reliability and good conduct. We have to have that decency. Austria is a country, not a tabloid.”

The BBC has named the astronomer one of the 100 most inspiring and influential women of 2021 — what an asset her presence would be for Austria! We know so little about each other, yet exchange and learning could be so easy, and so necessary, for everyone. But we make it so difficult.

Meanwhile, Amena Karimyan has been stuck in Pakistan for over three months. She is still being denied permission to travel on to Austria. There have been countless attempts, conversations, and promises; plans and efforts have been made. But her situation remains unchanged — or rather, it grows more perilous with every day she has to stay in Islamabad.

The West is appalled by the Taliban’s backwardness and brutality; we are outraged by their hostility to science, culture and women. But we not only let it happen, we legitimize their actions by failing to help those who are persecuted by their regime. At the same time, the world is currently lacking what it needs most: the opposite of ignorance. We should all reach for the stars.

January 2022 – Turning point and new beginning

We hear and read plenty of touching words in Austria around the Christmas holidays, and 2021 is no exception. But these points of light in the dark skies of the Alpine Republic only shine within their narrow confines. Once again we see that there is another way when we learn about a decision shortly after the New Year. In Germany, Amena is put on the list of Afghans who are under particular threat. From that moment on, everything happens very quickly. At an appointment in the German embassy in Islamabad, they take her information in order to issue her a German visa. We’re surprised and incredibly relieved. Shortly after, she is told her date of departure — in three days! Although I understand what a binding commitment that is, there’s still some trepidation. Too often, seemingly insurmountable obstacles have arisen at the last minute. Will it all go well this time? The day before departure, she receives her visa. She breathes a sigh of relief. Once again she packs her things, now the time has come. A long road lies ahead of her; she cannot leave behind the horrors of what she has experienced. Much later, she will write, “I lost myself.” One last photo at the Islamabad airport, then she boards a plane for the first time in her life. It takes her to Europe, to Germany, in safety. Late at night on January 6-7, Amena’s message lights up my phone: “I am here.”

Eine Antwort

nacht über österreich für afghanische astronomin – ausreisser.mur.at

[…] Link zur englischen Version. […]