Tully Purser ◄

It seems like such an official name for this wobbling mess that swells beneath my flesh, like some overfilled water balloon, all knotted up at the neck and perilously close to bursting.

Disenfranchised grief.

I wonder how far the metaphor goes—is it my fate too, to rupture?

I seem to leak instead. One of those duds that had a microscopic hole somewhere before it was filled, invisible to the eye but bleeding itself out nonetheless. My cheeks are constantly wet, tears and sweat congealing into a sticky sheen, and I don’t care if they’ve become glue for stray hairs and grime; my hands are already coated in it after days of stroking unwashed fur.

I don’t want to wash it away.

There’s no time to consider it anyway, because Melba is thrashing again.

At first we thought her fits were more seizures; her head would jerk and shake, and her legs would flail like she was dreaming, so we’d cradle her head and whisper soothing words, and all of the tears would come back like they hadn’t been shed an hour before.

But the convulsions had given way to compulsions to move and she’d struggle and writhe until we lifted her up.

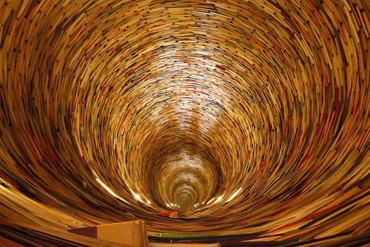

And once she was up, the circles began.

With the seizures’ departure went all sense of balance, so she couldn’t walk straight, and she couldn’t stand still. She paced in sloppy, ritualistic circles; each step an attempt to catch herself in this cruel and continuous fall.

But she couldn’t do it alone. We’d cleared the furniture the day before, while waiting for the vet, and laid out rugs on the slick floor so her claws had something to grip. When she became restless we’d carry her there and walk; propping up her stumbling body with our own.

Circles and circles and circles.

My mind still carries the dizziness of those cyclical walks.

And the foul smell of canned tuna where we’d dip our fingers, coaxing Melba to eat, to lick it off even though she had lost control of her tongue. A week before she would have gobbled it up.

For 13 years Melba’s eyes were bright; soft eyes that carried summer days and campfires and nights spent warming ourselves before the woodstove on Christmases and New Years past. But despite ceaseless nursing and depthless love, her eyes are hollow and black. The light is gone, and Melba along with it.

The sun has been replaced by heatless fluorescent lighting, but the rest of the world doesn’t notice. I have class in the morning. A presentation next week. My classmates are asking each other whether they understood the reading.

I stare at my lap.

The white hairs on my clothes are crisp, so crisp that everyone must notice. It must be the first thing they see. Do you have a dog? And I will spill my sorrow everywhere, wet and messy and impossible to scoop back into the nice and tidy package I’ve been hiding behind my back.

But no one asks that. The hairs have been there every day, no matter how many times I’d gone over them with the lint roller. No one asked then, and they’re no whiter to anyone else now.

Still, I weave them into my shirt a little bit tighter.

I don’t think I’ll buy another roller.

Class must be over because I’m carried by the tide of moving students, but I’m dropping my bones behind me like papers from a torn bookbag. Grief sloughs off my shoulders, pooling and oozing and leaving a sludgy snail’s trail in my wake.

It reeks.

Urine and slobber and antiseptic smother memories of sun-warmed, dusty fur that always smelled a bit like static; like that old tv set where zaps would bounce off my fingertips when I touched the screen.

We got rid of that tv ages ago. Donated it, I think, probably “salvaged for parts”. I’m not sure if I would call that a salvation.

But the static is gone, and the grief-smell is snaking its way through the folds of my clothes, my hair, the in-between spaces of my cells. My hands clamor to claw away the stench but there’s only skin and the smell permeates every layer.

Like an onion, I think.

And I hate onions.

Melba did too.